Aging with Intellectual Disability: Age-Based Health Planner

Enter your information and click "Plan My Aging Journey" to see personalized recommendations.

Key Recommendations:

- Annual comprehensive health reviews

- Regular medication reviews with pharmacist

- Maintain a life-story record

- Develop a crisis plan

- Encourage social engagement

| Age Range | Health Focus | Support Actions |

|---|---|---|

| 40–49 | Baseline screening (blood pressure, cholesterol, dental) | Set up a trusted caregiver network; start a medication list. |

| 50–59 | Increase monitoring for osteoporosis and type 2 diabetes | Consider home-care package; review advance care directive. |

| 60–69 | Annual cognitive assessment; vision/hearing check | Explore residential or supported living options if mobility declines. |

| 70+ | Focus on fall prevention, nutrition, and end-of-life preferences | Activate respite services; ensure legal documents are current. |

When people think about intellectual disability is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, they often focus on childhood. But the reality is that millions of adults live with this condition, and they will age just like anyone else. Understanding aging with intellectual disability helps families, caregivers, and professionals plan for a healthier, safer later life.

Why Aging Matters for Everyone

Age‑related changes are universal: bone density drops, vision and hearing decline, metabolism slows, and the risk of chronic illnesses rises. For most people these shifts happen gradually, and routine health check‑ups catch problems early.

However, the baseline for someone with an intellectual disability can be different. Cognitive and adaptive skills may already be below average, and certain co‑existing health issues are more common. When the natural aging process adds another layer, the combined effect can be confusing if you don’t know what to look for.

How Aging Shows Up Differently in Intellectual Disability

Research from Australian disability health services (2023) shows three main ways the aging curve diverges:

- Earlier Onset of Age‑Related Conditions: Conditions such as osteoporosis, type2 diabetes, and hypertension often appear 5-10years earlier than in the general population.

- Accelerated Functional Decline: Mobility and self‑care skills may deteriorate faster, especially if muscle tone was already low.

- Higher Risk of Cognitive Deterioration: The prevalence of dementia is roughly double that of peers without an intellectual disability.

These patterns mean that standard age‑based screening schedules need to be adjusted. For example, bone‑density scans that start at 65 for the general public might be recommended at 55 for many adults with an intellectual disability.

Common Health Concerns in Later Life

Below are the health issues you’ll most likely encounter as your loved one advances in age. Each bullet includes a practical tip for early detection.

- Cardiovascular disease: Blood pressure and cholesterol should be checked at least annually. Watch for unexplained fatigue or shortness of breath.

- Vision and hearing loss: Routine audiology and ophthalmology exams every 2years help maintain independence.

- Mobility problems: Look for increased reliance on walkers or frequent falls. Physical therapy can preserve strength.

- Dementia: Memory lapses, mood swings, or changes in routine may signal early dementia. Early referral to a neuro‑psychologist is key.

- Dental disease: Poor oral hygiene can exacerbate heart issues. Dental checks every 6months are advisable.

- Epilepsy: Seizure frequency can increase with age; medication doses may need tweaking.

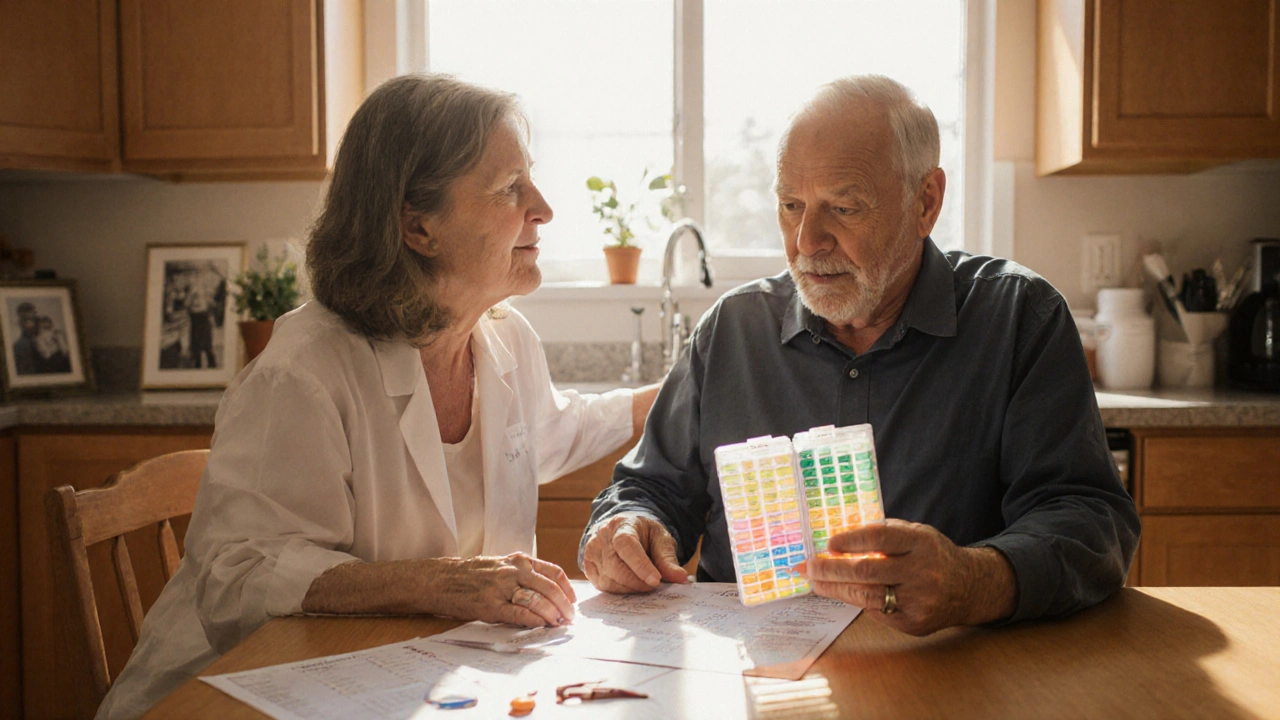

Medication Management and Care Coordination

Polypharmacy is a big challenge. Many adults with an intellectual disability take medications for seizure control, mental health, and chronic diseases simultaneously. Side‑effects can become harder to spot when communication is limited.

To keep medication safe:

- Maintain a master medication list, updated after every doctor's visit.

- Use a pill‑organiser with large, color‑coded compartments.

- Schedule regular medication reviews with a pharmacist who understands intellectual disability needs.

When a new drug is added, monitor for changes in behavior, appetite, or sleep patterns for at least two weeks.

Support Services and the Role of the Caregiver

The caregiver is often the central figure in managing health, appointments, and daily routines. Yet caregivers can become overwhelmed, especially as demands increase with age.

Key services that lighten the load include:

- Community Disability Support Teams: Offer multidisciplinary assessments and link to allied health professionals.

- Home Care Packages: Provide funded assistance for personal care, nursing, or domestic chores.

- Respite Care: Short‑term stays in specialist facilities give families a break.

When selecting a provider, ask about staff training in both aging and intellectual disability, and whether they have protocols for emergency medication administration.

Legal and Financial Planning for Later Life

Early planning prevents crises. Two essential documents are:

- Advance Care Directive: States wishes about medical treatment, including life‑sustaining measures. It can be completed with a supported decision‑making approach.

- Guardianship or Enduring Power of Attorney: Names a trusted person to make legal or financial decisions when capacity declines.

Both documents should be reviewed every 2-3years, especially after a major health event.

Practical Tips for Families and Professionals

- Schedule annual comprehensive health reviews that include physical, dental, vision, hearing, and mental health assessments.

- Maintain a life‑story record (photos, favorite activities, communication preferences) to help health providers understand the person’s background.

- Develop a crisis plan outlining who to call, medication details, and emergency contacts.

- Encourage regular physical activity suited to ability level - swimming, adapted yoga, or daily walks improve cardiovascular health and mood.

- Stay connected socially: Loneliness accelerates cognitive decline. Community groups, disability‑specific clubs, or online platforms can help.

Quick Checklist: Aging with Intellectual Disability

| Age Range | Health Focus | Support Actions |

|---|---|---|

| 40-49 | Baseline screening (blood pressure, cholesterol, dental) | Set up a trusted caregiver network; start a medication list. |

| 50-59 | d>Increase monitoring for osteoporosis and type2 diabetesConsider home‑care package; review advance care directive. | |

| 60-69 | Annual cognitive assessment; vision/hearing check | Explore residential or supported living options if mobility declines. |

| 70+ | Focus on fall prevention, nutrition, and end‑of‑life preferences | Activate respite services; ensure legal documents are current. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Do people with intellectual disabilities live longer now?

Yes. Improvements in medical care, inclusive policies, and better support services have increased life expectancy by5-10years over the past two decades. However, the gap between the general population and those with an intellectual disability still exists.

How early should I start screening for dementia?

For adults with an intellectual disability, begin formal cognitive screening at age45or5years earlier than the usual 65‑year benchmark, especially if there is a family history of dementia.

What if my loved one refuses medication?

Use a supported decision‑making approach: explain benefits in simple language, offer choices (e.g., pill versus liquid), and involve a trusted caregiver. If refusal continues and health is at risk, consult a health professional about possible legal avenues.

Are there specific residential options for aging adults with ID?

Yes. Many states in Australia offer “Supported Living” facilities that blend independent apartments with on‑site care. Look for places accredited for aging populations, with staff trained in dementia care and mobility assistance.

How can I help my parent stay socially engaged?

Join local disability clubs, attend community art classes, or use video‑calling platforms with familiar friends. Consistency is key - schedule activities weekly and tailor them to the person’s interests.

Aging, in its inexorable march, compels us to confront the very architecture of identity; when intellectual disability enters this equation, the scaffolding of support must be re‑examined with surgical precision. First, we must recognize that chronological age is but a superficial marker, while biological and cognitive trajectories diverge in unpredictable patterns. Second, the principle of early detection, long held as a cornerstone of preventive medicine, acquires amplified relevance, for conditions such as osteoporosis may manifest half a decade earlier in this cohort. Third, the integration of multidisciplinary teams-physicians, pharmacists, therapists, and social workers-should not be an afterthought but a pre‑emptive safeguard against polypharmacy pitfalls. Moreover, the legal apparatus, encompassing advance care directives and enduring powers of attorney, must be instituted well before the shadow of capacity loss looms. Equally vital is the cultivation of a life‑story archive; such narratives provide clinicians with contextual anchors that transcend sterile clinical data. From a functional standpoint, mobility assessments ought to be scheduled at least biennially, with a bias toward earlier intervention whenever a decline in gait or balance is noted. Vision and hearing screenings, often relegated to the periphery, should be performed with the same rigor as cardiovascular checks, given their profound impact on autonomy. When addressing mental health, we must adopt a dual lens that captures both affective symptoms and the heightened prevalence of dementia, the latter of which may arise up to ten years sooner than in neurotypical peers. Pharmacological stewardship, therefore, demands a systematic review each twelve months, with an emphasis on dose adjustments that account for age‑related metabolic shifts. In parallel, caregivers must be equipped with respite resources; burnout is not merely an occupational hazard but a systemic failure that jeopardizes patient safety. Financial planning, often shrouded in complexity, should be demystified through regular consultations with disability‑aware advisors to secure sustainable funding streams. Community inclusion, contrary to popular misconception, remains a therapeutic modality; social engagement mitigates cognitive erosion and fosters a sense of purpose. Finally, the ethos of person‑centered care dictates that all interventions be calibrated to the individual's preferences, abilities, and cultural background. In sum, aging with intellectual disability is not a peripheral concern but a central pillar of inclusive health policy, demanding foresight, coordination, and unwavering compassion.