When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy and see a price tag that’s 80% lower than the brand-name version, you’re holding a generic drug. But how did it get there? Behind every small, plain pill is a highly regulated, science-heavy process that ensures it works just like the expensive brand-name drug - but costs a fraction of the price. This isn’t magic. It’s precision manufacturing, strict testing, and decades of regulatory science.

What Makes a Drug "Generic"?

A generic drug isn’t a copy. It’s an identical twin. It must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, same dosage form (pill, injection, cream, etc.), and same route of administration (oral, topical, inhaled) as the original brand-name drug. The FDA requires that generics deliver the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate. That’s called bioequivalence. If a generic drug’s absorption rate falls outside the 80%-125% range of the brand-name drug, it’s rejected.

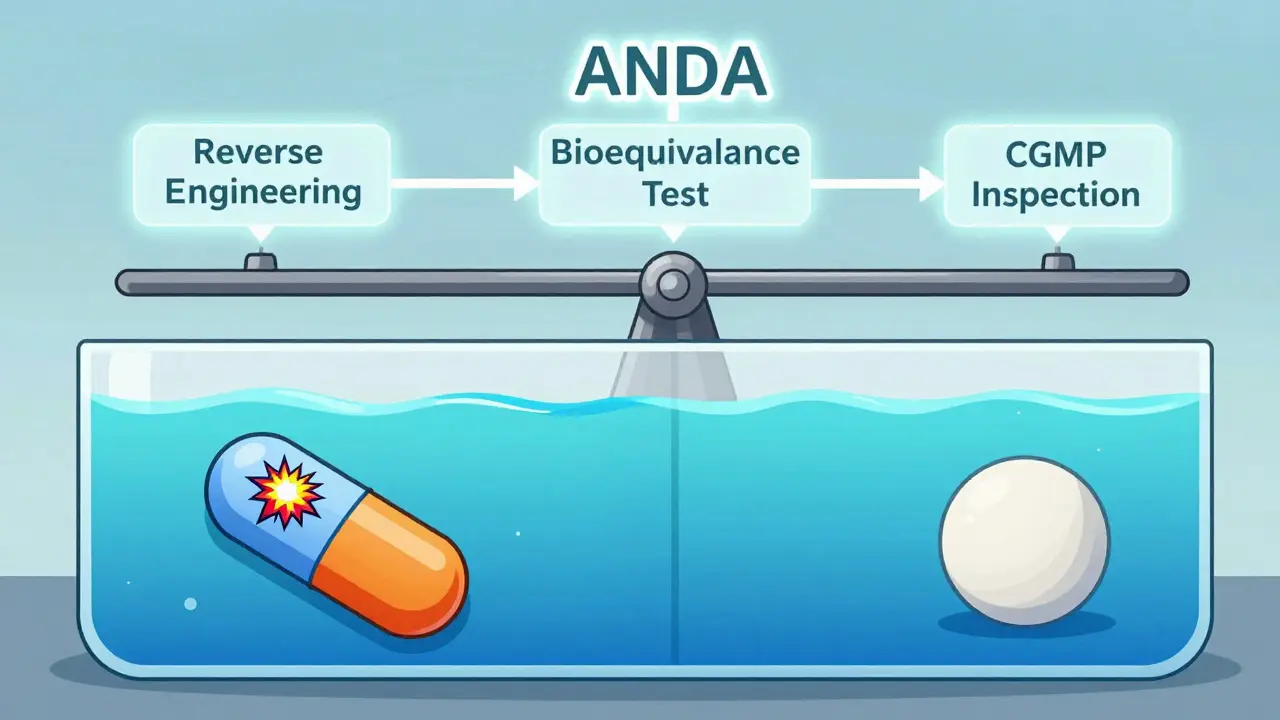

Here’s the kicker: generics don’t need to repeat the original clinical trials. That’s because the safety and effectiveness of the active ingredient were already proven. Instead, generic manufacturers use the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway - created by the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. This system lets them skip costly human trials and focus on proving they can make the exact same medicine, consistently.

The Seven-Step Manufacturing Process

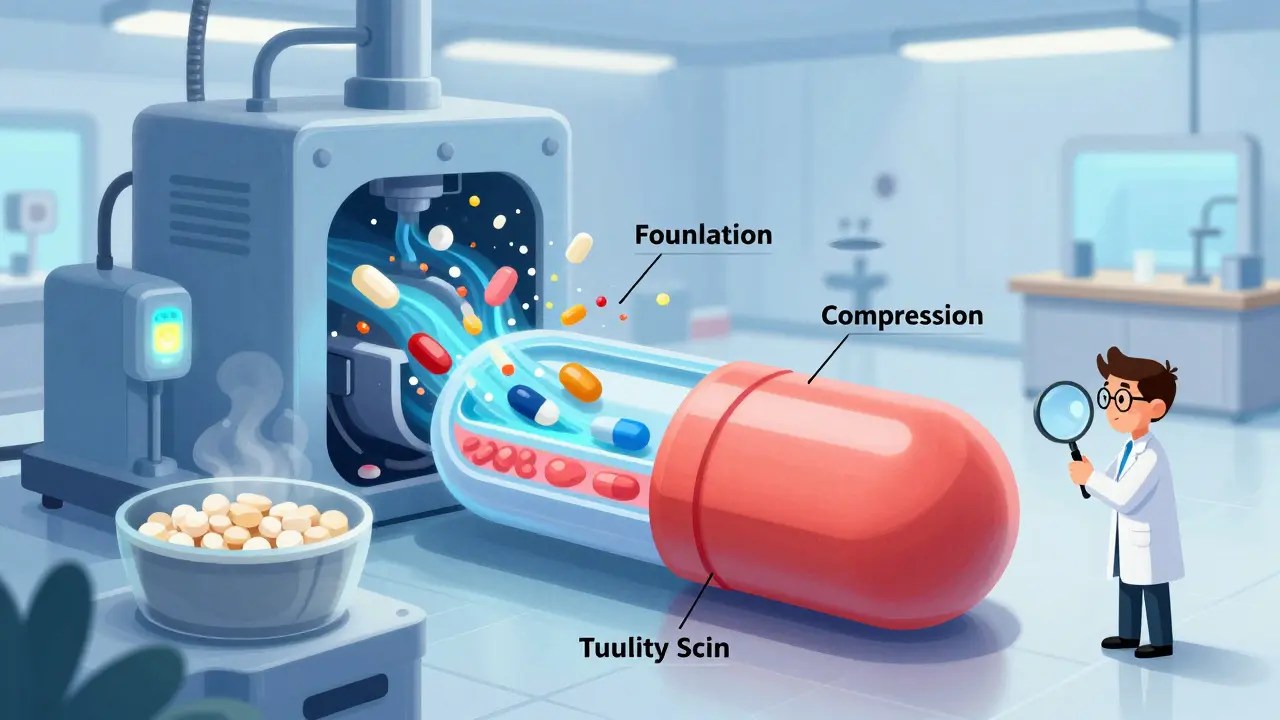

Manufacturing a generic drug isn’t just mixing chemicals. It’s a tightly controlled, seven-stage operation that must meet Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP). These rules aren’t suggestions - they’re legally enforceable standards set by the FDA. Facilities must maintain strict temperature (20-25°C), humidity (45-65% RH), and air cleanliness (ISO Class 5-8 cleanrooms). One tiny mistake - like a change in particle size of an excipient - can ruin an entire batch.

- Formulation: The process starts with reverse-engineering the brand-name drug. Manufacturers analyze its composition - not just the active ingredient, but all the inactive ones (excipients) too. These include fillers, binders, and coatings that affect how the pill dissolves. Even a small change in lactose or starch can alter how quickly the drug releases in your body.

- Mixing and Granulation: Raw materials are blended in large, calibrated mixers. For tablets, the mixture is turned into granules - tiny clumps that flow better during pressing. This step uses Quality by Design (QbD) principles, which identify Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and link them to Critical Process Parameters (CPPs). If the granule size is off by 10%, the tablet might crumble or dissolve too slowly.

- Drying: Wet granules are dried in ovens or fluid-bed dryers. Moisture content must be under 1%. Too much moisture, and the tablet degrades. Too little, and it becomes brittle. This stage is monitored with real-time sensors.

- Compression and Encapsulation: Dry granules are pressed into tablets using high-speed tablet presses. Each tablet must weigh within ±5% (for tablets under 130mg) or ±7.5% (for 130-324mg) of target weight. Capsules are filled with powder or pellets using automated fillers. Machines check every 15 minutes for weight, hardness, and thickness.

- Coating: Tablets are often coated to mask taste, protect the drug from stomach acid, or control release. A delayed-release coating, for example, keeps the drug from dissolving until it reaches the small intestine. Coating thickness is measured with laser sensors. A coating that’s too thin? The drug might break down too early. Too thick? It won’t dissolve properly.

- Quality Control: Every batch undergoes at least 15 tests before release. These include identity checks (is it the right drug?), assay (is the dose correct?), dissolution (does it release properly?), and purity (are there contaminants?). Dissolution testing alone involves placing tablets in simulated stomach fluid and measuring drug release over time. If even one tablet fails, the whole batch is destroyed.

- Packaging and Labeling: Pills are sealed in blister packs or bottles with child-resistant caps. Labels must list the generic name, strength, manufacturer, and lot number. Importantly, U.S. trademark law forbids generics from looking exactly like brand-name drugs - so color, shape, and imprint are different, even if the medicine inside is identical.

Approval: The ANDA Pathway

Before a generic hits shelves, it must pass FDA review. The ANDA process takes 3-4 years and costs $5-10 million - a tiny fraction of the $2.6 billion it takes to develop a new drug. Here’s how it works:

- Submission: The manufacturer files an ANDA, which includes full details of the manufacturing process, analytical methods, and bioequivalence data.

- Bioequivalence Testing: 24-36 healthy volunteers take both the generic and the brand-name drug in a crossover study. Blood samples are taken over 24-72 hours to measure peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC). Both must fall within the 80%-125% range with 90% confidence.

- Facility Inspection: The FDA inspects the manufacturing site. In 2023, 37% of warning letters cited inadequate investigation of out-of-specification results. If the facility doesn’t meet CGMP standards, approval is delayed.

- Labeling Approval: The generic’s label must match the brand’s in dosage, warnings, and contraindications - even if the brand’s label changes later.

- Post-Approval Monitoring: Manufacturers must report adverse events and conduct stability testing for at least 12 months after approval. Changes to the formula or process require FDA notification.

Complex generics - like inhalers, topical creams, or extended-release tablets - take longer. A 2022 case study showed one manufacturer spent 7 years and $47 million to match a single topical steroid’s skin absorption. That’s why only 12% of ANDAs in 2015 were for complex drugs - now it’s 35%.

Why Some Generics Fail - And How Quality Is Maintained

Not all generics are created equal - but not because they’re inferior. The issue lies in raw materials and supply chains. Over 78% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for U.S. generics come from China and India. A batch of lactose from one supplier might have finer particles than another. That small difference can change tablet hardness and dissolution rate.

One pharmacist on Reddit, with 12 years in manufacturing, said: “The biggest headache? Excipient variability. A 5% change in particle size can throw off your entire batch.”

That’s why leading manufacturers invest heavily in quality systems. Dr. Reddy’s requires 160 hours of initial GMP training and 40 hours yearly. Every deviation - even a machine glitch - must be investigated within 24 hours. Change control systems track every tweak, and stability testing runs for years.

Still, recalls happen. In 2021, Teva recalled 14 generic products due to CGMP violations at a Puerto Rico plant. But these are exceptions. A 2023 survey by the Association for Accessible Medicines found 89% of pharmacists have high confidence in generic quality. Only 3% reported any meaningful difference in patient outcomes.

The Bigger Picture: Cost, Access, and Future Trends

Generics make up 90% of U.S. prescriptions but only 19% of total drug spending. Over the past decade, they’ve saved the healthcare system over $1.7 trillion. In 2023, a generic version of Sovaldi (sofosbuvir) cut hepatitis C treatment costs from $84,000 to $28,000 - without sacrificing efficacy.

But challenges remain. Price erosion is brutal. For simple generics, 15-20 competitors can drive prices down 70-80% in two years. That’s why some manufacturers exit the market. Meanwhile, complex generics - with only 2-5 competitors - hold higher margins and slower price drops.

Technology is changing the game. The FDA’s Emerging Technology Program now approves continuous manufacturing - where drugs are made in one unbroken flow, not in batches. Vertex’s cystic fibrosis drug using this method hit 99.98% batch acceptance, up from 95% with traditional methods. AI is also being used: Pfizer’s pilot program cut visual inspection errors by 40% in 2023.

Looking ahead, the FDA is rolling out new guidances for nasal sprays, eye drops, and topical products. And with $75 billion in branded drugs set to lose patent protection by 2027 - including Eliquis and Stelara - demand for generics will only grow.

Final Thoughts

Generic drugs aren’t cheap because they’re low quality. They’re cheap because the system is designed to remove unnecessary costs - not cut corners. Every pill you take was made under strict rules, tested against the original, and approved by regulators who demand proof, not promises. The process is complex, expensive, and meticulous - but it works. And for millions of people, it’s the only way they can afford life-saving medicine.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also prove bioequivalence - meaning they deliver the same amount of medicine into your bloodstream at the same rate. The FDA inspects manufacturing facilities and monitors adverse events. Studies show no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs.

Why do generic pills look different from brand-name pills?

U.S. trademark law prohibits generic drugs from looking identical to brand-name drugs. This prevents confusion and protects brand identity. So while the medicine inside is the same, generics often have different colors, shapes, or markings. These changes don’t affect how the drug works - only its appearance.

Can different generic brands of the same drug work differently?

In theory, no. All generics must meet the same FDA bioequivalence standards. But because they may use different inactive ingredients (excipients), some patients report slight differences in how a drug feels - like faster digestion or a different taste. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin or levothyroxine - even small changes can matter. If you notice a difference, talk to your pharmacist or doctor.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved?

On average, the FDA reviews an ANDA in 10 months under GDUFA IV (as of 2023), down from 17 months previously. But complex generics - like inhalers or extended-release tablets - can take up to 36 months. The timeline depends on the drug’s complexity, the quality of the application, and whether there are patent disputes.

Why are so many generic drugs made in China and India?

Manufacturing APIs (active ingredients) at scale is cheaper in countries with lower labor and regulatory costs. Over 78% of the APIs used in U.S. generics come from China and India. The FDA inspects these facilities just like U.S. ones - and over 90% of inspected foreign plants meet CGMP standards. But this reliance raises concerns about supply chain vulnerabilities, especially during global disruptions.