When you're on Medicaid, getting your generic prescriptions shouldn't be a mystery-but in practice, it often feels like one. The rules change depending on where you live. What’s covered in California might not be covered in Texas. What’s free in New York could cost you $8 in Florida. This isn’t about confusion-it’s about a patchwork system where each state runs its own version of the same federal program. And if you’re trying to stay on your meds without breaking the bank, you need to know how your state actually works.

Every State Covers Generics-But How They Do It Varies Wildly

Yes, every single state and Washington D.C. covers outpatient generic drugs under Medicaid. That’s not up for debate. Federal law doesn’t force them to, but all 51 jurisdictions chose to because it saves money and keeps people healthy. The real question isn’t whether generics are covered-it’s how they’re managed.

At least 41 states require pharmacists to substitute a generic drug when it’s available and approved as therapeutically equivalent. That means if your doctor writes a prescription for brand-name lisinopril, the pharmacist can-and often must-give you the generic version unless you or your doctor specifically object. But here’s the catch: some states only allow substitution if the brand and generic cost at least $10 apart. Others require prior authorization even for generics if they’re not on the preferred list.

Colorado, for example, legally mandates generic substitution unless the brand drug is cheaper or the patient has been stable on it for months. In contrast, states like California take a lighter touch. Their Medi-Cal program rarely blocks generic access unless there’s a clear clinical reason. That’s not random-it’s policy design. States with stricter rules are trying to control costs. States with looser rules are trying to reduce administrative burden.

Formularies: The Hidden Rulebook You Never Saw Coming

Every state has a formulary-a list of drugs it will pay for. But not all formularies are created equal. Some are open, meaning almost any FDA-approved generic gets covered. Others are tightly managed, with tiers, step therapy, and prior authorization requirements that make filling a prescription feel like climbing a ladder blindfolded.

Most states use a tiered system. Tier 1 is your basic generic-low cost, no hassle. Tier 2 might be a brand-name drug or a generic that’s more expensive than others in its class. Tier 3? That’s usually specialty meds, but sometimes it’s a generic that’s been flagged for overuse or cost spikes. CVS Caremark, which manages pharmacy benefits for 15 states, lists Tier 1 as generic drugs in their 2025 Medicaid formulary. But what’s in Tier 1 in one state might be in Tier 2 in another.

Step therapy is another big one. At least 32 states require you to try one or two cheaper, preferred drugs before they’ll cover the one your doctor actually prescribed. For example, if you have arthritis and your doctor wants to prescribe a specific NSAID, your state might force you to try ibuprofen and naproxen first-even if you’ve already tried them and they didn’t work. This isn’t about being difficult. It’s about cost. But it also causes delays. A 2024 University of Pennsylvania study found that when Medicaid patients get stuck in step therapy loops, their hospital admissions jump by nearly 13%.

Prior Authorization: The Bureaucratic Hurdle

Prior authorization is where things get messy. It’s not just for expensive brand-name drugs anymore. In many states, even generic versions of common medications require pre-approval if they’re not on the preferred list.

Colorado’s Health First Colorado program requires prior authorization for almost every non-preferred drug. That includes generics for diabetes, blood pressure, and even some antibiotics. The process usually takes 24 hours-if you’re lucky. In other states, it can take up to three days. Meanwhile, you’re out of pills. Providers spend an average of 15.3 minutes per patient just filling out these forms, according to the American Medical Association. That’s over $8,200 a year in lost time for every doctor.

Some states have simplified it. Massachusetts, for instance, got a 4.6 out of 5 rating from providers for how clear and easy their formulary is. Mississippi? Only 2.8. That’s not about how many drugs are covered-it’s about how easy it is to find out what’s covered.

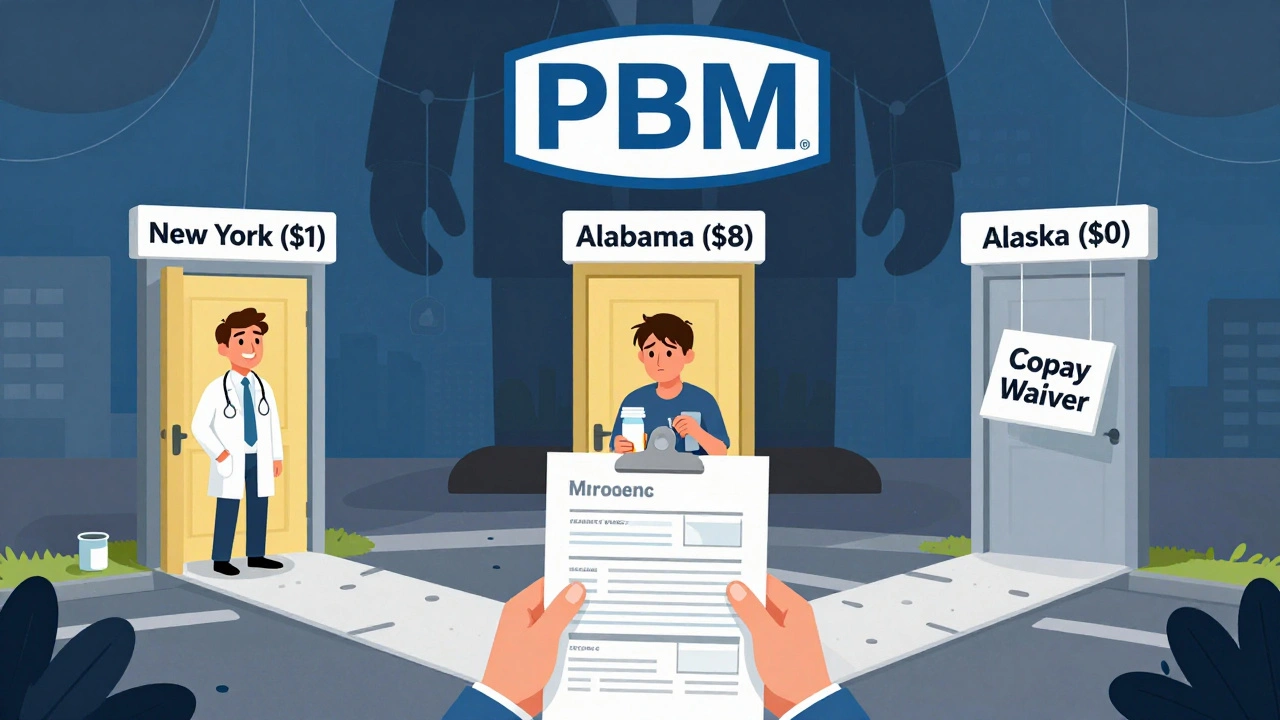

Copays: From Free to

Even if your drug is covered, you might still pay. Federal rules let states charge copays for generics-up to $8 for people earning below 150% of the federal poverty level. But many states charge less. Some charge nothing at all.

In New York, most Medicaid beneficiaries pay $1 for a 30-day supply of a generic. In Ohio, it’s $2. In Alabama, it’s $8. In Alaska, it’s $0. Why the difference? It’s political. States with higher copays are trying to discourage “overuse.” States with lower or no copays are focused on adherence. Studies show that even a $2 copay can cause people to skip doses of chronic meds like insulin or blood pressure pills. That’s why states like Vermont and Minnesota keep copays low or eliminate them entirely.

Pharmacist Substitution Rules: Who Decides?

When a pharmacist hands you a generic instead of the brand, who made that call? In 28 states, the pharmacist must document that the generic is therapeutically equivalent. In 12 states, they can swap it without telling anyone. In 46 states, they follow the FDA’s “AB” ratings for therapeutic equivalence. But not all states use the same version of the FDA list.

Therapeutic interchange is another layer. Some states let pharmacists swap a generic for a different generic in the same class if it’s cheaper-even if the doctor didn’t prescribe it. For example, if you’re on generic amlodipine and a cheaper version comes in, your pharmacist might switch you without asking. But in states without therapeutic interchange rules, you’re stuck with whatever the doctor wrote-even if it costs $5 more.

Who’s Running the Show? PBMs and the Hidden Middlemen

Most states don’t manage their own pharmacy benefits. They hire companies called Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx manage Medicaid pharmacy programs in 37 states. That means the rules you see on your state’s website might actually be written by a private company in Minnesota or Texas.

PBMs negotiate rebates with drugmakers, set formularies, and decide which generics get preferred status. And while they claim to save money, critics say they create complexity. One state might list a generic as preferred because the PBM got a big rebate. Another state might not list it at all because the rebate was too small. The result? Two identical prescriptions, two different outcomes.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

Big shifts are coming. In December 2024, CMS proposed a rule that would require Medicaid to cover anti-obesity medications like semaglutide. If it passes, it could affect nearly 5 million people. But there’s a catch: these drugs are expensive, and many are still brand-name. States are worried they’ll be forced to pay without enough federal help.

Meanwhile, a proposed law could remove inflation rebates for most generic drugs from the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. That would cost states an estimated $1.2 billion a year. If that happens, expect more prior authorizations, higher copays, and tighter formularies.

On the bright side, more states are testing value-based purchasing for generics. Michigan tied rebates to patient adherence for diabetes meds and cut costs by 11.2%. That’s the future: paying for results, not just pills.

What You Need to Do Right Now

Don’t wait until your prescription runs out. Here’s what to do:

- Check your state’s Medicaid formulary. Most have a searchable database online. Look for “Preferred Drug List” or “PDL.”

- Call your pharmacy and ask: “Is this generic on the preferred list?” If not, ask if they can switch to one that is.

- If your drug requires prior authorization, ask your doctor to submit it early. Don’t wait until your last pill is gone.

- If you’re paying $8 for a generic, ask if you qualify for a copay waiver. Some states offer exemptions for chronic conditions.

- Keep a printed copy of your formulary and your medication list. Providers change, and not all know your state’s rules.

Medicaid is supposed to be a safety net. But when the rules are hidden, inconsistent, and confusing, that net has holes. Knowing how your state works isn’t just helpful-it’s essential.

Do all states cover generic drugs under Medicaid?

Yes. All 50 states and Washington D.C. cover outpatient generic drugs under Medicaid. Federal law doesn’t require it, but every state has chosen to include pharmacy benefits because it’s cost-effective and improves health outcomes. However, how they cover them-through formularies, copays, prior authorization, and substitution rules-varies widely.

Can I be forced to switch to a different generic drug?

Yes, in 28 states, pharmacists can switch you to a different generic version of the same drug if it’s cheaper and therapeutically equivalent-even if your doctor didn’t prescribe it. This is called therapeutic interchange. In other states, you can only be switched to the exact generic your doctor wrote. Check your state’s pharmacy laws to know your rights.

Why does my generic drug need prior authorization?

Even generics can require prior authorization if they’re not on your state’s preferred list. States use prior authorization to control costs, especially for drugs that have had price spikes or are being overused. For example, a generic version of a common antibiotic might need approval if it’s more expensive than other options in its class. It’s not about the drug being unsafe-it’s about whether it’s the most cost-effective choice.

How much can I be charged for a generic drug?

Federal rules allow states to charge up to $8 for a 30-day supply of a non-preferred generic drug if your income is below 150% of the federal poverty level. Many states charge less-$1, $2, or nothing at all. Some states waive copays for chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension. Always ask your pharmacy or Medicaid office if you qualify for a copay reduction.

What if my state won’t cover a generic my doctor prescribed?

If your state’s formulary doesn’t cover the generic your doctor prescribed, you can ask for an exception. Your doctor can submit a prior authorization request explaining why the specific drug is necessary-for example, if you had side effects from other versions or if it’s the only one that works for you. If denied, you can appeal. Many states have formal appeals processes, and patient advocacy groups can help.

Are there any generic drugs Medicaid never covers?

Yes. Federal law bars Medicaid from covering certain drug classes, even if they’re generic. These include drugs for weight loss, erectile dysfunction, fertility, and cosmetic use. So even if a generic version exists, Medicaid won’t pay for it. Some states also exclude certain high-cost generics if they’re not on the preferred list, but they can’t exclude entire categories unless they’re federally prohibited.

Can I get help navigating my state’s Medicaid formulary?

Yes. Most states have a Medicaid pharmacy helpline. Nonprofits like the National Health Law Program and state health advocacy groups also offer free assistance. Some community pharmacies have Medicaid specialists who help patients understand formularies and prior authorizations. Don’t try to figure it out alone-help is available.

Just wanted to say this is one of the clearest breakdowns I’ve seen on Medicaid generics. I’ve been stuck in prior auth loops for months and this finally made sense. Thanks for the actionable steps-especially checking the PDL. I’m printing this out.