Every year, thousands of athletes push through pain to compete-sometimes with the help of a shot that stops inflammation cold. Methylprednisolone is one of those drugs. It’s not magic, but for many players, it’s the difference between sitting out and stepping onto the field. Yet behind the quick relief lies a tangled web of risks, ethical debates, and long-term consequences that few talk about openly.

What Methylprednisolone Actually Does

Methylprednisolone is a synthetic corticosteroid. It’s not a painkiller like ibuprofen. Instead, it shuts down the body’s inflammatory response at the cellular level. When you tear a muscle, sprain an ankle, or get tendonitis, your immune system sends signals to swell, heat, and hurt the area. That’s supposed to protect you. But in sports, that same swelling can sideline an athlete for weeks.

Methylprednisolone blocks those signals. It reduces swelling, calms nerve irritation, and eases pain-not by numbing it, but by removing the cause. That’s why it’s used in acute injuries like tennis elbow, severe bursitis, or flare-ups of chronic conditions like rheumatoid arthritis in athletes. A single intramuscular or intra-articular injection can bring relief within 24 to 48 hours. For someone preparing for a championship game, that’s priceless.

It’s not used for daily pain. It’s reserved for short-term, high-stakes situations. Doses are typically 40 to 120 mg, given as a one-time shot or over three to five days. The goal isn’t to cure-it’s to buy time.

Why Athletes Rely on It

Think about a college basketball player with a swollen knee. She’s averaging 22 points a game. The playoffs start in three days. Surgery isn’t an option. Rest means missing the season. She gets a methylprednisolone injection into the joint. By morning, she’s walking without a limp. By afternoon, she’s shooting free throws. By game night, she’s playing 35 minutes.

This isn’t rare. A 2023 study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine found that over 60% of professional athletes in contact sports received at least one corticosteroid injection during their career. In the NFL, it’s common for players to get shots before the playoffs. In the NBA, players like LeBron James and Kevin Durant have openly discussed using them to manage chronic joint issues.

The appeal is simple: fast, effective, and non-surgical. Unlike opioids, it doesn’t cause drowsiness or addiction. Unlike NSAIDs, it doesn’t wreck the stomach lining with repeated use. For a team doctor, it’s a reliable tool when time is short and stakes are high.

The Hidden Costs

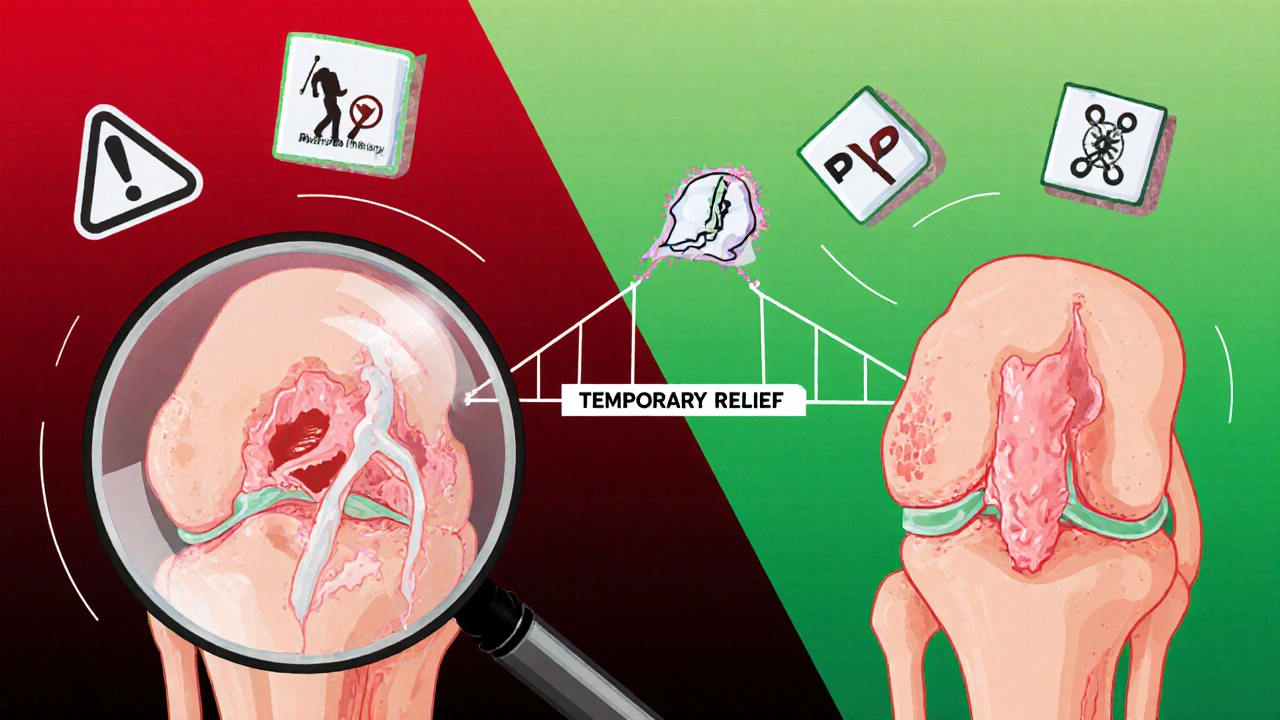

But here’s what no one tells you: methylprednisolone doesn’t heal. It hides.

When inflammation is suppressed, the body stops signaling damage. That means an athlete might push a torn ligament, a hairline fracture, or degenerating cartilage harder than they should. The pain is gone-but the injury isn’t fixed. By the time the effects wear off, the damage has often worsened.

There’s also the risk of tissue breakdown. Repeated injections can weaken tendons. The Achilles tendon is especially vulnerable. Studies show that athletes who get more than two corticosteroid injections in the same joint over a year are at higher risk for tendon rupture. One 2022 analysis in Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine found that 17% of athletes who received multiple injections for shoulder tendinopathy later needed surgery for complete tendon tears.

And then there’s systemic effects. Even a single high-dose injection can spike blood sugar, raise blood pressure, and suppress the immune system for days. For a player recovering from a virus or dealing with stress, that’s dangerous. One Australian rugby player in 2024 developed a severe staph infection after a shoulder injection-his immune system hadn’t recovered.

The Ethical Gray Zone

Methylprednisolone isn’t banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). But that doesn’t mean it’s ethical to use.

There’s a big difference between treating a real injury and masking pain to compete when you shouldn’t. Teams and trainers sometimes use it as a performance enhancer-not to heal, but to extend playing time beyond what the body can safely handle. In youth sports, where pressure to perform is intense, parents and coaches may push for injections without understanding the long-term risks.

WADA allows it, but the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) both warn against its routine use. They say it should only be used when there’s confirmed inflammation and no safer alternatives. But in practice, guidelines are often ignored.

And then there’s the slippery slope: if methylprednisolone is okay, what about other anti-inflammatories? What about nerve blocks? Where do you draw the line between treatment and enhancement?

Alternatives That Actually Work

There are better ways to manage sports injuries-ones that don’t risk long-term damage.

- Physical therapy: Targeted rehab strengthens surrounding muscles, reduces joint stress, and improves movement patterns. It takes longer, but it fixes the root cause.

- PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma): Uses the athlete’s own blood to stimulate healing. Studies show it’s more effective than steroids for chronic tendon injuries like jumper’s knee.

- Shockwave therapy: Proven for plantar fasciitis and tennis elbow. It triggers natural repair without drugs.

- Cryotherapy and compression: Simple, safe, and effective for reducing swelling after acute trauma.

- Gradual return-to-play protocols: The best way to avoid reinjury is to let the body heal properly-even if it means missing a game.

Some teams, like the Melbourne Storm in the NRL, have shifted away from steroid injections entirely. Their injury rates have dropped by 30% since 2022. They now prioritize rehab over quick fixes.

When It Might Still Be Worth It

That doesn’t mean methylprednisolone has no place in sports medicine. There are times when it’s the right call.

For example:

- An elite runner with a flare-up of plantar fasciitis two weeks before a marathon-after six weeks of failed rehab.

- A soccer goalkeeper with severe elbow bursitis before the World Cup qualifiers.

- An athlete with autoimmune arthritis needing to compete while managing disease activity.

In these cases, the benefit outweighs the risk-but only if:

- The diagnosis is confirmed (via ultrasound or MRI).

- The injection is given by an experienced sports physician.

- It’s followed by a structured rehab plan.

- The athlete is monitored for side effects.

It’s not a shortcut. It’s a calculated tool-used sparingly, with full awareness of the trade-offs.

What Athletes Should Ask Before Accepting a Shot

If you’re offered a methylprednisolone injection, don’t just say yes. Ask these questions:

- What’s the exact diagnosis? Is it confirmed with imaging?

- How many injections have I had in this area before?

- What’s the plan after the injection? Will I get rehab?

- What are the risks for my sport and position?

- Are there alternatives I haven’t tried yet?

If the answer to any of these is vague, walk away. This isn’t a quick fix. It’s a medical decision-and it deserves more than a five-minute conversation in a clinic room.

The Bigger Picture

Sports medicine isn’t just about treating injuries. It’s about protecting athletes’ long-term health. Methylprednisolone has its place-but only if we stop treating it like a routine tool and start treating it like the powerful drug it is.

The best athletes aren’t the ones who play through everything. They’re the ones who know when to rest, when to heal, and when to say no-even when the crowd is screaming for them to play.

Is methylprednisolone banned in sports?

No, methylprednisolone is not banned by WADA. It’s allowed for use by athletes, even in competition. However, its use is restricted to therapeutic purposes and must be documented. Some leagues require a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) for systemic use, especially if taken orally or via IV. Injections into joints or muscles are generally permitted without a TUE, but guidelines vary by sport.

How long does methylprednisolone stay in your system?

The effects of a single injection can last from 1 to 4 weeks, depending on the dose and how your body metabolizes it. The drug itself clears from the bloodstream in about 2 to 3 days, but its anti-inflammatory action lingers longer because it alters cellular behavior. Blood tests won’t detect it after a week, but its impact on tissue healing can last much longer.

Can methylprednisolone cause weight gain or mood changes?

Yes. Even a single high-dose injection can cause temporary side effects like increased appetite, fluid retention, and mood swings. Some athletes report irritability, insomnia, or anxiety for a few days after the shot. These are more common with oral doses but can still happen with injections, especially in sensitive individuals. These effects usually fade within a week.

Is it safe to get methylprednisolone injections every season?

No. Repeated injections in the same joint significantly increase the risk of tendon rupture, cartilage damage, and bone weakening. Most experts recommend no more than two to three injections per joint per year, with at least 3 to 6 months between doses. Athletes who rely on them annually often end up needing surgery later. Long-term use is not a sustainable strategy for athletic longevity.

Do professional teams disclose when athletes get methylprednisolone injections?

Rarely. Teams usually keep this information private to avoid public scrutiny or questions about player health. Even though WADA doesn’t require disclosure for injections, some leagues have internal reporting systems. But in practice, unless there’s a major injury after the injection, it’s rarely made public. Fans often don’t know an athlete had a shot until they see them playing through pain.

man i saw a dude on the bench last season with a legit swollen knee and he got that shot before the 4th quarter

he came out and dropped 30 points like nothing

then he missed the next 3 games because his tendon felt like wet paper

we all cheered

no one asked what the cost was