Why Modified-Release Formulations Are Harder to Get Right

Not all pills are created equal. A regular tablet releases its medicine fast-within minutes. But a modified-release (MR) pill? It’s engineered to spread that release out over hours. Think of it like slow-dripping paint instead of splashing it all at once. This design helps keep drug levels steady in your blood, which means fewer side effects, less frequent dosing, and better control of chronic conditions like high blood pressure, epilepsy, or chronic pain.

But here’s the catch: when a generic version of an MR drug hits the market, it doesn’t just need to contain the same active ingredient. It has to behave the same way in your body. That’s where bioequivalence comes in. And for MR drugs, bioequivalence isn’t just about comparing AUC and Cmax like it is for regular pills. It’s a whole different level of complexity.

The Numbers Behind MR Drugs

About 35% of all approved generic drugs in the U.S. are modified-release formulations. That’s not a small slice-it’s a major chunk of the market, worth over $65 billion annually. These aren’t niche products. They’re the backbone of treatment for millions of people managing long-term illnesses.

Why do companies invest so much in MR? Because patients stick with them. Studies show adherence improves by 20-30% when you switch from three pills a day to one. That’s huge. Missed doses lead to hospitalizations, especially with drugs like warfarin or antiepileptics. So getting the release profile right isn’t just science-it’s safety.

How Bioequivalence Testing Differs for MR Drugs

For a regular tablet, you give one dose to volunteers, take blood samples for 24 hours, and check two things: total exposure (AUC) and peak concentration (Cmax). If both fall within 80-125% of the brand-name drug, you’re good.

For modified-release? That’s not enough.

Take a drug like zolpidem CR (Ambien CR). It has two parts: one that kicks in fast to help you fall asleep, and another that lasts longer to keep you asleep. You can’t just look at the overall AUC. You have to measure the early part (0-1.5 hours) and the late part (1.5 hours to infinity) separately. Both need to be within 80-125%. If the fast-release part is too slow, you won’t fall asleep. If the slow part is too strong, you might feel groggy the next day.

The FDA now requires this kind of partial AUC analysis for any multiphasic MR product. The EMA also looks at things like half-value duration and midpoint duration time. These aren’t just technical details-they’re clinical safeguards.

Alcohol, Dissolution, and the Hidden Risks

Here’s something most people don’t know: some extended-release pills can dump their entire dose if you drink alcohol while taking them. It’s called dose dumping. And it’s dangerous-sometimes deadly.

The FDA requires alcohol testing for any ER product with 250 mg or more of active ingredient. That includes common painkillers like oxycodone ER or morphine ER. In the lab, they test the pill in a solution that’s 40% alcohol. If more than 25% of the drug releases in the first hour under those conditions, the product fails.

Between 2005 and 2015, seven ER products were pulled from the market because of this issue. One was a generic version of a popular opioid. Patients took it with a glass of wine and ended up in the ER with overdose symptoms.

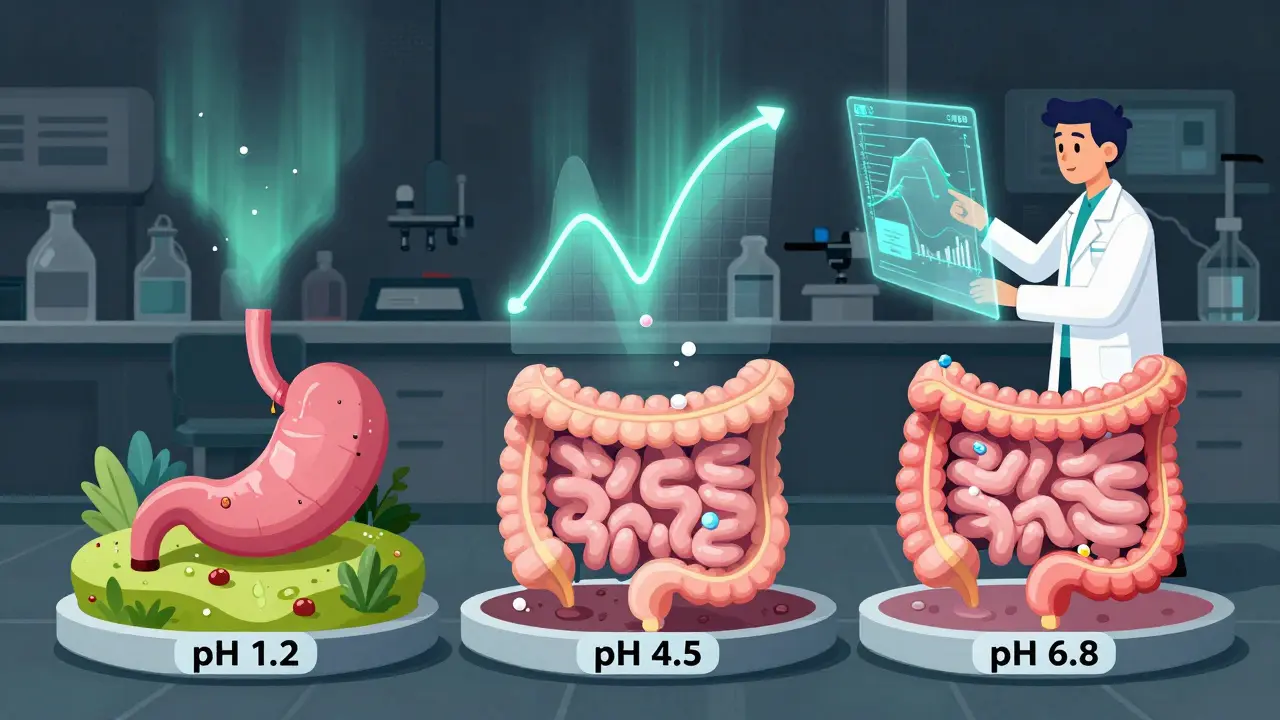

Dissolution testing is another hurdle. For ER tablets, regulators demand tests at three pH levels: stomach acid (pH 1.2), small intestine (pH 4.5), and upper colon (pH 6.8). The release profile must match the brand at each level. If it doesn’t, the generic won’t work the same way in different people’s guts. One formulation scientist at Teva told a forum that 35-40% of early oxycodone ER attempts failed this test. That’s not a small setback-it’s a dead end.

Regulatory Differences Between the FDA and EMA

The U.S. and Europe don’t agree on everything when it comes to MR bioequivalence.

The FDA says: single-dose studies are enough. They argue that multiple-dose studies add noise-accumulation, compliance issues, variable absorption-and don’t improve accuracy. Over 90% of approved ER generics since 2015 used single-dose designs.

The EMA says: sometimes you need steady-state studies. If the drug builds up in your body (accumulation ratio >1.5), then you need to test after several days of dosing. That’s because the way the drug behaves over time matters more than just one dose.

And then there’s biowaiver. The FDA lets you skip human studies if your dissolution profile matches the brand at all three pH levels and your product meets certain criteria. The EMA is stricter. They require more proof, like similarity factor (f2) ≥50 across all pH levels. For beaded capsules, the FDA only requires one pH test. The EMA still wants three.

These differences mean a generic that passes in the U.S. might fail in Europe. That’s why big manufacturers often run parallel studies-just to be safe.

When the Numbers Aren’t Enough: Highly Variable Drugs

Some drugs just vary wildly between people. Warfarin, for example. One person needs 2 mg. Another needs 10 mg. That’s not because of the pill-it’s because of their genes, diet, liver function.

For these, standard 80-125% limits don’t work. If you use them, you’ll reject good generics or approve bad ones.

That’s where Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE) comes in. It’s a smarter system. Instead of a fixed range, the acceptable window expands based on how variable the brand-name drug is. The FDA caps this at 57.38% variability. So if the brand varies a lot, the generic can vary a bit more too-without risking safety.

But here’s the catch: RSABE adds 6-8 months to development time. The math is complex. The software is expensive. And regulators demand full documentation. One Mylan pharmacologist said it’s like solving a puzzle with half the pieces missing.

Why Some Generics Still Fail

It’s not just about chemistry. It’s about precision.

In 2012, a generic version of Concerta (methylphenidate ER) was rejected because it didn’t release enough drug in the first 2 hours. Kids needed the quick onset to focus in school. The generic was too slow. Even though overall exposure was fine, the early release was off. The FDA said no.

Another failure point? Strength scaling. If you want to make a 40 mg version based on a 20 mg version, you have to prove the release profile scales proportionally. Forty-five percent of applicants fail this on the first try. It’s not about the active ingredient-it’s about how the coating, beads, or matrix behaves at different doses.

And then there’s the cost. Developing a generic MR drug costs $5-7 million more than a regular one. A single-dose bioequivalence study runs $1.2-1.8 million. That’s why only big companies do it. Small biotechs? They don’t have the budget.

What’s Next for Modified-Release Drugs

The future is getting smarter. The FDA is working on a new 2024 guidance for complex MR products-things like gastroretentive tablets (that float in the stomach) and multiparticulate systems (hundreds of tiny beads). These are harder to test because they don’t behave like traditional pills.

More companies are using PBPK modeling-computer simulations that predict how a drug moves through the body. In 2022, 68% of major pharma firms used it for MR development. It’s not perfect yet, but it cuts down on failed trials.

And then there’s IVIVC-In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation. If you can prove that how a pill dissolves in a lab perfectly predicts how it behaves in a person’s body, you might not need human studies at all. The FDA has accepted this for 12 products since 2019, including an extended-release version of paliperidone.

By 2028, IQVIA predicts MR formulations will make up 42% of all prescription sales. Aging populations, chronic diseases, and demand for better compliance will keep driving growth.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient taking a generic MR drug, you should know: it’s not just a cheaper version. It’s a complex product that had to pass a tougher test. Most of them work just fine. But if you’ve ever noticed a change in how you feel after switching brands-feeling more tired, more anxious, or having breakthrough symptoms-it’s worth talking to your doctor.

If you’re in the industry, the message is clear: don’t cut corners. The science is precise. The regulators are watching. And the stakes? They’re not just financial. They’re personal.

Are generic modified-release drugs as safe as brand-name ones?

Yes, when they’re properly developed and approved. The FDA and EMA require rigorous testing to ensure that generic MR drugs release the drug at the same rate and time as the brand. This includes testing under different pH levels, with alcohol, and measuring partial drug exposure. Most generics pass these tests and perform just as well. But because MR formulations are more complex, failures can happen-especially if the release profile isn’t matched precisely. If you notice changes in effectiveness or side effects after switching, talk to your pharmacist or doctor.

Why do some MR generics get rejected by the FDA?

The most common reasons are failure to match the release profile at key timepoints, especially for multiphasic drugs like zolpidem CR or methylphenidate ER. Other reasons include inadequate dissolution testing across pH levels, poor alcohol interaction results, or failure to demonstrate proportional scaling across strengths. About 22% of MR generic applications were initially rejected between 2018 and 2021 due to these issues. It’s not about the active ingredient-it’s about how it’s delivered.

Can I take a modified-release generic with alcohol?

It depends on the drug. For extended-release products with 250 mg or more of active ingredient, alcohol can cause the pill to release its entire dose at once-called dose dumping. This can lead to overdose. The FDA requires manufacturers to test for this. If the product label warns against alcohol, don’t mix them. Even if it doesn’t say so, it’s safest to avoid alcohol with any extended-release medication unless your doctor says it’s okay.

What’s the difference between ER and MR?

ER stands for extended-release-it means the drug is released slowly over time. MR is broader-it includes ER, but also delayed-release (DR), sustained-release (SR), and multiphasic (like two bursts). So all ER drugs are MR, but not all MR drugs are ER. For example, a delayed-release pill might not release anything until it reaches the intestine. A multiphasic pill might release some drug right away and more later. Bioequivalence testing adjusts for these differences.

Why does bioequivalence testing for MR drugs cost so much?

Because it’s more complicated. Instead of one or two blood draws, you need many more-sometimes every hour for 48 hours. You need specialized dissolution equipment that tests at multiple pH levels and with alcohol. You need experts who understand partial AUC, RSABE, and IVIVC. A single-dose MR bioequivalence study costs $1.2-1.8 million, compared to $0.8-1.2 million for a regular one. The extra cost reflects the extra science required to ensure safety and effectiveness.

This is why generics are a gamble. I had a generic oxycodone ER that made me feel like I was drugged on a Tuesday. Then I switched back to brand and suddenly I could breathe again. The FDA says it's 'bioequivalent'-whatever that means. My body doesn't care about their math.