If you've ever spent time under the Australian sun without proper eye protection, you might have heard of 'Surfer's Eye'-a condition that's actually called pterygium. In Melbourne, where UV levels often hit 'extreme' on the index, this isn't just a beachside concern. About 12% of men over 60 in Australia have it, and for outdoor workers, the numbers jump even higher. But what exactly is this growth, and why does sun exposure trigger it? Let's break it down.

What is pterygium?

Pterygium is a noncancerous growth of the conjunctiva-the clear tissue covering the white part of your eye. It typically starts near the inner corner and spreads toward the pupil in a triangular shape, like a little wing (which is where the name comes from, from Greek 'pterygion'). This growth contains visible blood vessels and can range from a small, barely noticeable bump to a thick, opaque layer that blocks vision. According to MedlinePlus, it's defined as a growth that starts in the conjunctiva and covers the sclera (white part) before moving onto the cornea. When it grows over the cornea, it can cause blurry vision or astigmatism.

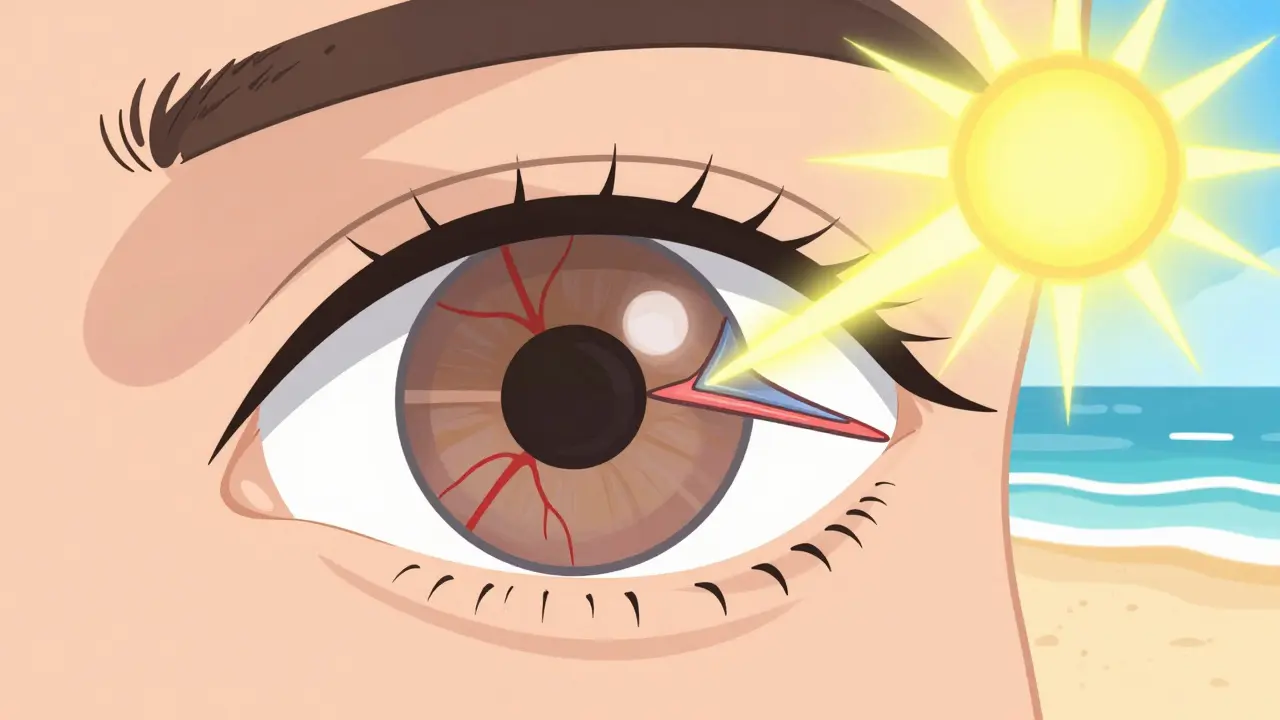

How sun exposure leads to pterygium growth

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun is the main culprit behind pterygium. Research from the University of Melbourne shows that cumulative UV exposure exceeding 15,000 joules per square meter increases the risk of developing pterygium by 78%. This is why people living near the equator-within 30 degrees of it-have a 2.3 times higher risk compared to those at higher latitudes.

In Australia, where UV levels frequently reach 'extreme' (index 11+), the risk is especially high. The World Health Organization states that UV index above 3.0 requires eye protection. In tropical regions, this threshold is exceeded about 200 days a year. For surfers, construction workers, or farmers, daily UV exposure without protection can lead to pterygium over time. A Reddit user named 'SurfDude23' shared: 'After 15 years of surfing without eye protection, I developed pterygium in both eyes. The constant irritation made contact lenses unbearable, and my vision started getting blurry when it reached the pupil.'

Recognizing symptoms and diagnosis

Pterygium often starts as a small, fleshy bump on the white of the eye. Early signs include redness, irritation, or a gritty feeling like sand in the eye. As it grows, you might notice blurred vision or see distortion in your sight if it covers the cornea. Doctors diagnose it during a routine eye exam using a slit-lamp-a specialized microscope that magnifies the eye 10-40 times. No blood tests or scans are needed; the visual appearance of the growth extending from the sclera onto the cornea is enough for diagnosis.

It's important to distinguish pterygium from pinguecula, another common eye growth. According to Palmetto Ophthalmology Associates, 'a pinguecula is confined only to the conjunctiva' whereas 'as it extends to the cornea it is termed a pterygium.' Pinguecula is more common in outdoor workers (70% prevalence) but doesn't grow onto the cornea like pterygium does.

Preventing pterygium: Simple steps for eye protection

Prevention is straightforward but often overlooked. The Better Health Channel recommends two key actions: wearing UV-blocking sunglasses and a wide-brimmed hat whenever outdoors. Look for sunglasses labeled with ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards-these block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays. Regular sunglasses aren't enough; they need to wrap around the sides to block peripheral UV light.

Dr. Ann Marie Griff from Healthline explains: 'The exact cause isn't known, but too much exposure to UV light is the strongest environmental risk factor.' For people in high-risk areas like Australia, wearing protective eyewear daily is critical. A patient on Healthgrades noted: 'Wearing UV-blocking sunglasses daily has stopped the progression of my early-stage pterygium according to my last two annual check-ups.'

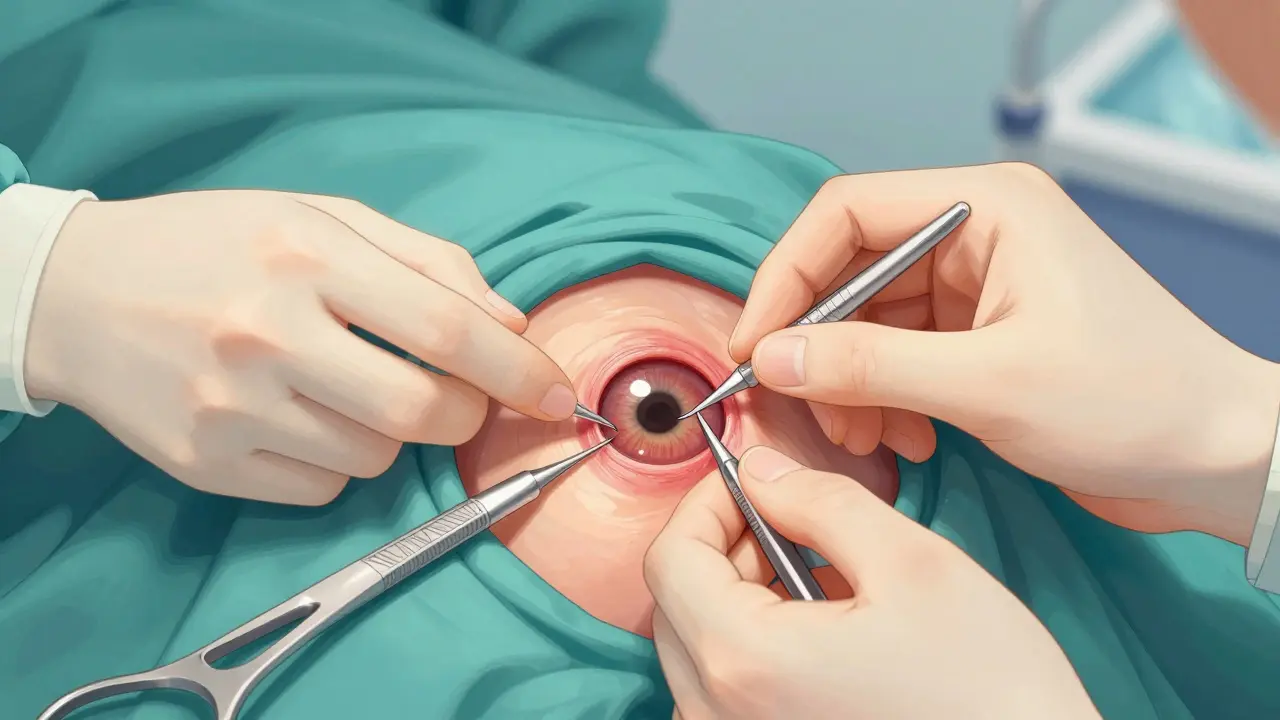

Surgical treatments for pterygium

When pterygium affects vision or causes discomfort, surgery is the only way to remove it. There are several techniques, each with different success rates:

- Surgical excision with mitomycin C: The growth is removed, and a drug called mitomycin C is applied to the area to reduce recurrence. This lowers recurrence rates from 30-40% to 5-10%.

- Conjunctival autograft: A piece of healthy conjunctiva from another part of the eye is stitched over the removal site. This has the lowest recurrence rate at 8.7% according to a 2022 meta-analysis.

- Amniotic membrane transplantation: A newer technique using donor amniotic membrane to cover the area. European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons guidelines (2023) recommend this for recurrent cases, with 92% success in preventing regrowth.

A 2023 FDA-approved product, OcuGel Plus, is now used for post-surgery comfort, showing 32% greater symptom relief than standard artificial tears. However, recovery isn't instant. Patients often experience discomfort for 2-3 weeks and need steroid eye drops for up to 6 weeks. A RealSelf.com user shared: 'The surgery took 35 minutes, but the steroid drops regimen for 6 weeks was more challenging than expected.'

Recovery and potential complications

After surgery, your eye will be red and sensitive for a few days. Most people return to work within a week, but full healing takes about 4-6 weeks. Common complications include inflammation (68% of surgeons report this as the main issue) and recurrence. Without proper follow-up care, recurrence rates can be as high as 30-40%. That's why doctors stress using prescribed eye drops consistently and avoiding sun exposure during recovery. A 2022 National Eye Institute survey found 32% of surgical patients reported regrowth within 18 months, highlighting the importance of ongoing monitoring.

Real-world experiences

From the trenches of patient communities, here's what people say:

- 'After years of surfing without eye protection, my vision got blurry. Surgery fixed it, but the recovery was tough,' says 'SurfDude23' on Reddit.

- 'Switching to UV-blocking sunglasses stopped my pterygium from growing. No surgery needed,' shared 'OutdoorPhotog' on r/optometry.

- 'The redness during healing was embarrassing, but the clear vision afterward was worth it,' noted a 4.2/5-rated review on Healthgrades.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can pterygium cause blindness?

No, pterygium itself doesn't cause blindness. However, if it grows large enough to cover the cornea, it can lead to astigmatism or block vision. Early treatment prevents this progression.

Is surgery the only treatment option?

Surgery is the only way to remove pterygium once it's formed. However, for small growths that don't affect vision, doctors often recommend monitoring and UV protection to prevent further growth. Medications like steroid eye drops may help reduce inflammation but won't eliminate the growth.

How long does recovery take after surgery?

Most patients return to daily activities within a week, but full healing takes 4-6 weeks. During this time, you'll use prescribed eye drops to prevent infection and inflammation. Redness and irritation typically subside after 2-3 weeks, but it's important to avoid sun exposure and follow your doctor's instructions carefully.

Can pterygium come back after surgery?

Yes, recurrence is possible. Without additional treatments like mitomycin C or conjunctival autografts, recurrence rates can be 30-40%. With these techniques, rates drop to 5-10%. Consistent UV protection after surgery is crucial to prevent regrowth.

What's the difference between pterygium and pinguecula?

Pinguecula is a yellowish growth confined to the conjunctiva (the white part of the eye), while pterygium extends onto the cornea. Pinguecula is more common (70% of outdoor workers) but doesn't usually affect vision. Pterygium, though less common, can grow large enough to interfere with sight and requires medical attention.

UV protection is crucial. Wrap-around sunglasses block peripheral light which is often overlooked. The stats show a significant drop in pterygium cases when proper eyewear is used consistently.